In 2022, seeking medical treatment, and finding ways to streamline the process, are on the forefront of public discussion. In many ways it feels like we’re experiencing unprecedented access to medical care, and that people are more conscious of their health than ever before. We trust our medical providers to take care of us, and to diagnose and solve problems. Perhaps most importantly, we trust that medicine will work, but face an increasingly obvious reality where this is not always the case. In the midst of the COVID pandemic, health professionals are cautioning against a silent pandemic that is ever growing.

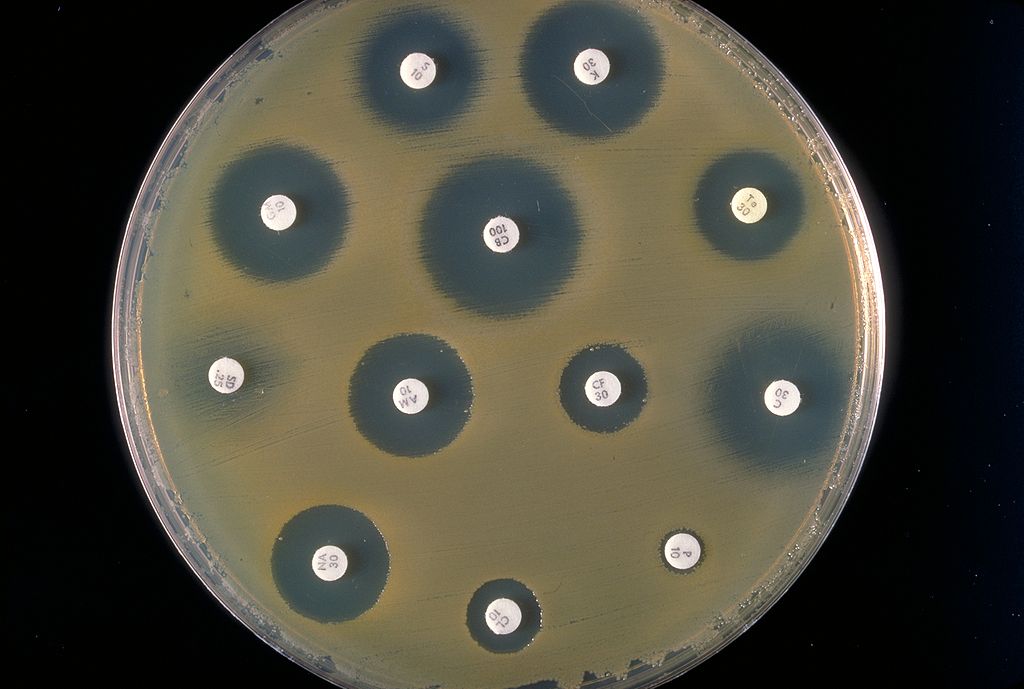

Antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, happens when bacteria, fungi, parasites or viruses change in a way that makes them resistant to the medication currently used for their treatment. This is something that affects every societal domain, from humans and pets, to livestock and agriculture. AMR is an insidious and growing threat that can be deadly. On a macro scale, it impacts the environment, food security, animal welfare and the very backbone of modern medicine. All of these factors converge to make antimicrobial resistance one of the most urgent and threatening public health problems facing the world today.

One immediate reaction to learning about AMR may be the suggestion that we treat illnesses with more or different antimicrobials. A closer look, however, reveals that the overuse and misuse of antimicrobials in fact accelerates the problem. In addition, inappropriate use of antibiotics has been associated with an increased risk of side effects, length and severity of illness, risk of complications, and a higher mortality rate 1. It’s important to remember that AMR doesn’t always come wrapped in a neat box, or follow a linear path such as: a patient shows up at a hospital displaying symptoms of a bacterial infection, the patient is treated and the doctors subsequently discover antimicrobial resistance. In reality, many medical procedures are predicated on the idea that doctors will be able to treat infections that appear during or after the process, and that resistance won’t be encountered.

If AMR continues to grow in microbes, there are countless necessary and lifesaving procedures, such as organ transplants, cancer therapy and the treatment of chronic illness, that will be affected. Antimicrobial resistance is a global health challenge that is directly responsible for over 1 million deaths per year, and is associated with 5 times that number. Globally this is nearly as high as the annual death toll of HIV and malaria combined.

The burden of this statistic weighs most heavily on low- to middle- income communities, like sub Saharan Africa, due to a combination of limited access to medical resources, inappropriate prescribing behavior, unauthorized sales of antimicrobials, and inadequate drug regulation on counterfeits 2. In rural and low-resource areas it’s not uncommon to find people stockpiling partial prescriptions to take later, or taking strong antibiotics without a prescription at all as a preventative measure 3. In some cases, people will administer their own medication to their animals and livestock in order to combat potential illness that could affect their livelihood. Some of these actions, which may seem surprising to readers living in high-income communities, are also prevalent at home. Any plan implemented to address AMR would need to take into account the specific social, cultural and economic factors of individual regions in order to succeed.

So what are the possible solutions to such a large, looming and multi-faceted problem? Any health professional will tell you that the first steps are to take it seriously, collaborate across sectors, and act quickly. But how can we accomplish this?

One pathway to combat AMR lies in the development and use of new antimicrobials to which microbes have no resistance. However, the high cost and low incentives currently in place for pharmaceutical companies to produce new antibiotics create a profit-shaped obstacle, to the extent that several biotech companies that managed to develop new medicines have failed due to low revenues 4.

Another option would be to improve access and education surrounding use and misuse of antimicrobials by people around the world. Various governments and organizations across the globe have launched campaigns to educate and influence both prescribers and their patients on antimicrobials and health. But perhaps the most effective way to combat AMR is through stewardship of these medicines. As with the treatment of individual patients, response and treatment plans need to be tailored to regional factors so that each community receives local and standardized guidelines they can rely on. Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) ensure that people have clear recommendations and a reliable resource available to them. With proper implementation, ASPs could promote the judicial use of antimicrobials, and improve patient health and safety.

One may be tempted to read this information, take it in, acknowledge the problem and then simply move on. After all, it can feel like we are constantly learning about and processing new tragedies, with the next one always looming on the horizon. An educated reader might have decided this is a problem endemic to low-income countries, that it could never happen here. Maybe they share a link or donate some money, even mention to a friend that they read this terrible story the other day, do you know what’s happening in sub Saharan Africa? They have such a high rate of drug-resistant illnesses and medicines are so unaffordable and hard to acquire that they are saving up their pills and even feeding their own antibiotics to livestock. Perhaps they’ve even heard of AMR affecting someone they know. A friend of a friend’s aunt caught a ‘Superbug’ on vacation and had to be hospitalized in a foreign country. Stories like these can often take the shapes of old wives’ tales, and lend even more implausibility to the narrative.

Allow us to tell you a final story:

Picture a woman in North America. She is educated, healthy and informed. One night, while preparing dinner, she slices her finger and decides to head to the nearest emergency department to get stitches. She waits in the crowded hospital for several hours, with her open wound, before she is seen by a doctor. She is sent home shortly after.

This simple cut grows redder and hotter and more painful day by day. She develops a fever. Her children and her friends ask if the redness is spreading, if the cut looks swollen and greyish. Finally, she goes back to the hospital and is diagnosed with a hospital-acquired infection from her last visit, requiring immediate antibiotic therapy. This does not work. The bacteria with which she is infected, is commonly found on our skin and usually does not pose a problem. But when the opportunity arises, a particularly resistant strain of the bacteria common to healthcare settings, can wreak havoc.

What happens to this woman, who believes she was educated, healthy and hygienic? Perhaps she undergoes more extensive antibiotic treatment, requiring long term care and extensive surgeries. Perhaps she loses her hand. Maybe she never leaves the hospital again. This is not a small, localized problem.

The health implications of AMR are severe, globally reaching, and require immediate action.

Learn more about Firstline’s humanitarian mission, or get in touch with us.

References

-

1) Llor, C. & Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5(6):229-241. ↩

-

2) Ayukekbong, J.A., Ntemgwa, M. & Atabe, A.N. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017; 6(47) ↩

-

3) Nayiga, S. Denyer Willis, L. Staedke, S, & Chandler, C. Taking Opportunities, Taking Medicines: Antibiotic Use in Rural Eastern Uganda. Medical Anthropology 2022. ↩

-

4) Jack, A. Pressure grows for funding to tackle ‘silent pandemic’ of antimicrobial resistance. Financial Times 2021. ↩